A proof of Fermat’s Christmas Theorem using Minkowski’s Theorem

Theorem: An odd prime \(p\) can be expressed as

\[p = x^2 + y^2 \]

with \(x, y\) integers if \(p \equiv 1 \mod 4\)

Example: \(5 = 1^2 + 2^2\), \(13 = 2^2 + 3^2\), \(17 = 1^2 + 4^2\), \(29 = 2^2 + 5^2\)

Lemma 1: For every \(a\) where \(p \nmid a\) there exists \(b\) such that \(ab \equiv 1 \mod p\)

Example: For \(a = 2\) and \(p = 5\) we may choose \(b = 3\).

Proof by Bézout’s theorem: Since \(a\) and \(p\) are coprime there exists integer \(n\) and \(M\) such that \(an + pm = 1\) hence \(an \equiv 1 \mod p\). :)

Lemma 2: For all prime numbers \(p\), \((p-1)! \equiv -1 \mod p\).

Example: \(1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdot 4 \equiv 1 \cdot (2 \cdot 3) \cdot (- 1) \mod 5\)

Example: \[ \begin{align*} &1 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdot 4 \cdot 5 \cdot 6 \cdot 7 \cdot 8 \cdot 9 \cdot 10 \cdot 11 \cdot 12 \\ \equiv_{13} \quad & 1 \cdot (2\cdot7)\cdot(3\cdot9)\cdot(4\cdot10)\cdot(5\cdot8)\cdot (6\cdot11)\cdot(-1) \end{align*} \]

Something fishy is going on, every pair of numbers I put in brackets multiples to something \(1 \mod 13\). We can pair everything up with something else and have those multiply to \(1\) besides \(1\) and \(-1\). Leaving \(1 \cdot 1 \cdot 1 \cdots 1 \cdot (-1)\). So \(12! \equiv 1 \mod 13\)

Proof by pairing: Every number from \(1\) to \(𝑝 − 1\) is coprime to \(𝑝\) and hence pairs uniquely to some other number from \(1\) to \(𝑝 − 1\) to multiply to \(1\). Unique because \(𝑎𝑏 ≡1≡𝑎𝑐\) implies \(𝑎(𝑏 −𝑐) ≡ 0\) and hence \(𝑝 ∣ 0\) or \(𝑝 ∣ 𝑏 −𝑐\) neither of which can be true. The only two numbers which pair with themselves are \(𝑥\) where \(𝑥^2 ≡ 1\) hence \((𝑥 −1)(𝑥 +1) ≡ 0\) and so \(𝑥 ≡ ±1 \mod 𝑝\). The rest is trivial, you can do it yourself.

Lemma 3: For a prime number \(p \equiv 1 \mod 4\) , there exists \(n\) such that \[n^2 \equiv -1 \mod p\]

Proof: Let \(p = 4k + 1\) and consider \(n \equiv 1 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdots {2k}\). \[ \begin{align*} n^2 & \equiv_p 1 \cdot 2 \cdots (2k) \cdots (2k+1) \cdots (4k-2) \cdot (4k-1) \\ & \equiv (-1)^{2k} \cdot 1 \cdot 2 \cdots (2k) \cdot (2k+1) \cdots (4k-2) \cdot (4k-1) \\ & \equiv (-1)^{2k} (p-1)! \\ & \equiv (p-1)! \\ & \equiv (-1) \end{align*} \]

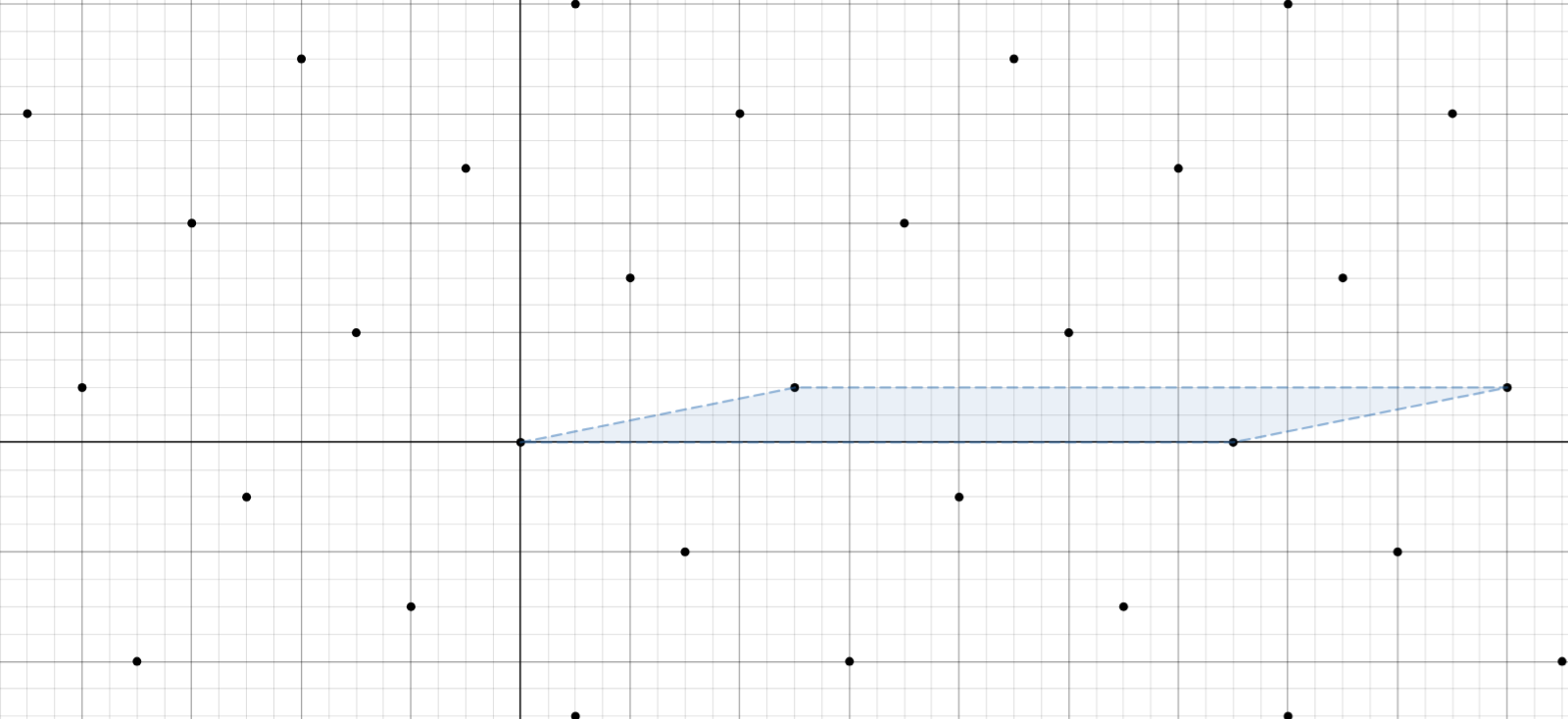

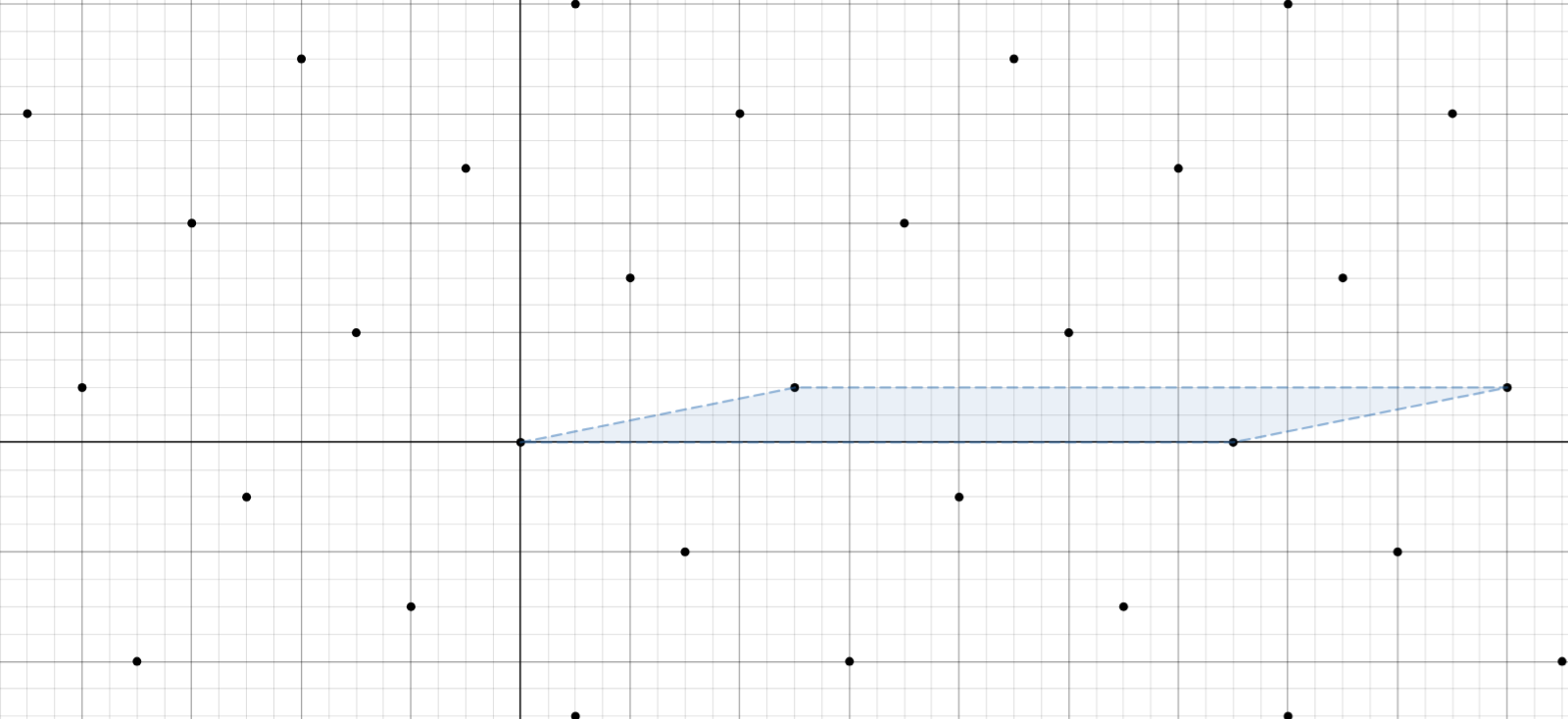

A lattice of points generated by \(n\) linearly independent vectors \(v_1, v_2, \dots, v_n\) is the set of all points of the form

\[ a_1 v_1 + a_2 v_2 + \dots + a_n v_n \]

where \(a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n\) are integers.

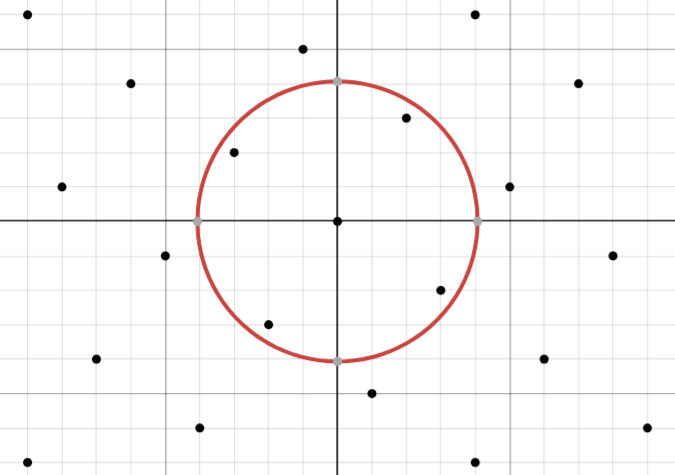

Minkowski’s Theorem: If a convex set in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) is symmetric about the origin and has volume \(2^n\) times the volume of the fundamental parallelepiped of a lattice in \(\mathbb{R}^n\), then the set contains a non-zero point of the lattice.

What this is really saying is that if you have a lattice of points in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) and you blow a big enough balloon about the origin, you will eventually hit a lattice point. More specifically in the case of \(\mathbb{R}^2\), if you have a lattice of points generated by two vectors \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) and you draw a circle with area of \(4 \cdot \text{area}(v_1,v_2)\) centered at the origin, then there must be a lattice point other than the origin inside that circle.

Proof of Fermat’s Christmas Theorem: Consider the lattice of points generated by the two vectors \(\begin{pmatrix} n \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\p \end{pmatrix}\). The area of the parallelogram spanned by these two vectors is \(p\). What’s important is that every lattice point \((x,y)\) is such that \(x^2 + y^2 \equiv 0 \mod p\).

Now draw a circle of radius \(\sqrt{\frac{4p}{\pi}}\) centered at the origin. The area of this circle is \(4p\) and so by Minkowski’s Theorem there must be a lattice point \((x,y)\) inside this circle other than the origin.

\(p \mid x^2 + y^2\) and \(x^2 + y^2 < \frac{4 p} \pi\). So \(x^2 + y^2 = p\) . So there must exist integers \(x\) and \(y\) such that \(p = x^2 + y^2\).